How many anime are there? 1/3

Let's start this series with one of the most discussed questions regarding the Japanese animation industry - the number of anime produced. While recurring discussions speak of a crisis of overproduction in the Japanese industry, the most natural response is to look for the raw number of animated productions. This is not entirely satisfactory, as we will see later, but it is still a good indicator of the current state of the industry. However, an important note to take into account: it may be difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the last three years - 2021, 2022 and 2023. Indeed, due to the pandemic, many productions have been delayed to another season or year, causing irregularities in pipelines.

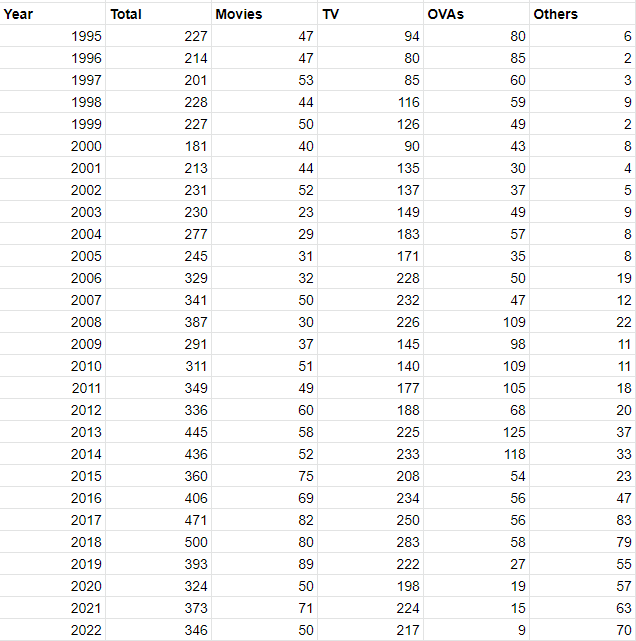

There are several ways to count the number of productions, most often focusing on television: the number of shows broadcast, the number of episodes or the number of minutes. Because of this centrality to television, it doesn't give a bird's-eye view of the industry as a whole. So, to start, I'm going to take the total number of productions, regardless of format; figures come from the Japanese Animation Database .

The general trend in the history of Japanese animation has been an increase in the number of productions. Here, starting with the 1990s, we see this trend, with few lasting declines. More precisely, there were 3 peaks: 2008 (387 works), 2013 (445) and 2018 (500). There has been a sharp decline since then, and even taking into account the disruption caused by the pandemic, it appears that things are roughly back to where they were in the 2000s. Whether this will rise again remains to be seen. .

The number of new anime productions per year, 1995-2022 (from the Japanese Animation Database "Anime TAIZEN"( https://animedb.jp/ ))

(Other surveys with different criteria exist and provide slightly different numbers from the Japanese Animation Database. However, regardless of the exact numbers, the trends are the same: see this survey by a Reddit user in 2020, which leads to a similar conclusion for TV series - a peak in 2018 followed by a decline in 2019 and 2020. Likewise for the number of films, as can be seen here .)

However, to better understand these numbers, it is necessary to break them down by format. Focusing on 2018, we can see that the high number of TV series was part of a longer trend, but the high number of productions in other formats was more exceptional for various reasons:

1) Following the release and unexpected success of Your Name , the number of feature films between 2017 and 2019 reached a record level

2) Web formats and releases (categorized under "other" here) were on the rise and had already peaked in 2017

3) 2018 is probably the last year the OVA format had any visibility, as the number of OVA releases dropped in subsequent years to now being less than 10

It is interesting to compare this situation with that of the 2020s. Of course, I cannot speak about future developments, but the number of feature films, expected to increase significantly following the success of Demon Slayer : Infinity Train , has not experienced as much growth between 2020 and 2022 as after Your Name . There was indeed a sudden increase in 2021, but it was likely largely due to all the films delayed in 2020 being pushed to the following year. In the short term, it is therefore possible to say that the number of cinematographic works has decreased rather than increased.

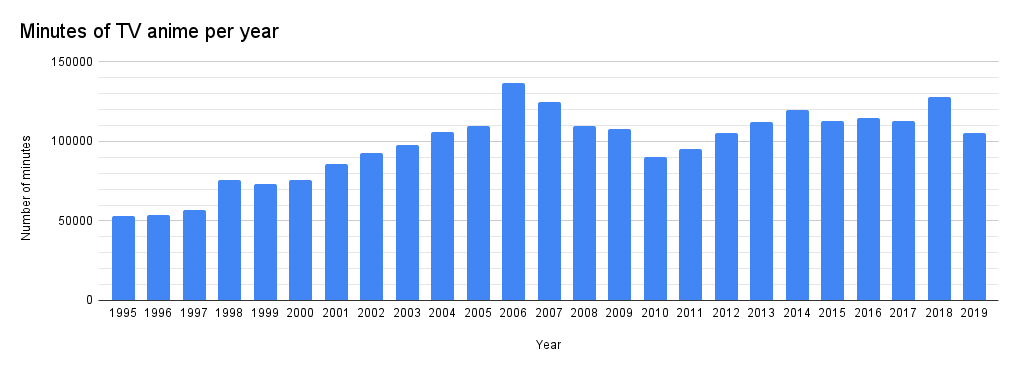

This first set of numbers is valuable because it provides a holistic overview of all formats. But if we focus on television, we risk confusion between the number of new titles and what is actually broadcast: long-lived shows, which last several years, necessarily disappear if we count the number new productions per year. This is why a more representative metric would be the number of episodes broadcast each year or, better yet, the number of minutes. The following chart, compiled by Hiromichi Masuda in 2021, provides the latter figure.

The number of minutes of animation broadcast on television per year, 1995-2019. Cited in Nagata, Daisuke & Matsunaga, Shintarô (2022). A sociology of industrial change: history of the experiences of facilitators

(産業変動の労働社会学 –アニメーターの経験史) .晃洋書房

This new dataset helps us put the previous one into perspective: although it may seem like 2008 represented a peak due to the amount of new work, it actually would have been 2006, with around 20,000 minutes of additional entertainment broadcast on television. In fact, the 2006 record hasn't been broken, even in 2018, which saw nearly 50 more TV shows hit the airwaves. The general shift in broadcasts from 2 lessons to 1 lesson may have inflated the overall numbers, but not the actual amount of content broadcast.

Again, this dataset only provides information for television works, and the numbers only go to 2019. However, the sharp decline in the number of minutes between 2018 and 2019 naturally coincides with that in the number of productions. Given this latest, erratic decline over the past 3 years, it is not unreasonable to conclude that, even when counting minutes, less TV anime is being produced than before .

But does this mean that “overproduction” is not a real problem? The answers to this are more complex; I'll quickly summarize them here, then get into the details later.

1) What matters is not so much the number of productions as the number of people . If the industry had enough people to produce a thousand television shows a year, there would be no problem; but the question is whether this is actually the case.

2) Anime production takes time. It is generally said that the overall time to produce a television series, from the initial planning stage to the actual broadcast, is around 2 to 3 years. In other words, it's not just about the number of works released each year, but those that are in production at the same time – which brings us to another, non-quantitative problem.

3) It's not just about numbers. More minutes of animation does lead to more time spent drawing and working for animators and staff, but the larger issue is scheduling. And, with one-course broadcasts, schedules must be restarted twice as often as with two-course broadcasts, making management much more complex. If all productions are done at the same time by the same people, their actual number is secondary – the situation will lead to general exhaustion in one way or another.

In the next installment, we'll look at data on anime studios. How many there are, how many staff they employ, and their sales and profits.